What can we do about the coming economic uncertainty due to AI?

We’re talking about risk here, and how to deal with it. This is something Mark Blyth has been thinking about for some time. Happily, he does his thinking with a good deal of wit and a nice dash of charm to boot. Charm notwithstanding, Mark happens to be an excellent and celebrated political economist, and economists are good for thinking about risk and how to mitigate it and develop hedges against it.

We’re talking about risk here, and how to deal with it. This is something Mark Blyth has been thinking about for some time. Happily, he does his thinking with a good deal of wit and a nice dash of charm to boot. Charm notwithstanding, Mark happens to be an excellent and celebrated political economist, and economists are good for thinking about risk and how to mitigate it and develop hedges against it.

Henry Shevlin is a philosopher who has been teaching AI Ethics at Cambridge University and leads the Consciousness and Intelligence project at the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence at Cambridge, which is a highly interdisciplinary research center addressing the challenges and opportunities posed by AI. As Professor Stephen Hawking said at the Centre’s launch, AI is “likely to be either the best or worst thing ever to happen to humanity, so there’s huge value in getting it right.”

Henry Shevlin is a philosopher who has been teaching AI Ethics at Cambridge University and leads the Consciousness and Intelligence project at the Leverhulme Centre for the Future of Intelligence at Cambridge, which is a highly interdisciplinary research center addressing the challenges and opportunities posed by AI. As Professor Stephen Hawking said at the Centre’s launch, AI is “likely to be either the best or worst thing ever to happen to humanity, so there’s huge value in getting it right.”

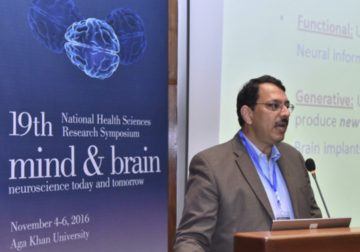

Ali Minai’s research interests include AI, neural networks, complex systems and networks, computational models of cognition and behavior, distributed multi-agent systems, and computational linguistics. Besides being a professor of computer science who has also served as President of the International Neural Network Society, Ali has recently been thinking and writing about AI Risk.

Ali Minai’s research interests include AI, neural networks, complex systems and networks, computational models of cognition and behavior, distributed multi-agent systems, and computational linguistics. Besides being a professor of computer science who has also served as President of the International Neural Network Society, Ali has recently been thinking and writing about AI Risk.

So we have invited Mark, Henry, and Ali, who’ve all been pondering how to deal with AI-specific economic risk, to a symposium to take place over a weekend (the formal part of the symposium will be on July 27) this summer in the Italian alps where they will exchange ideas from their diverse perspectives with a small and select group of guests. Read more »

Returning home after being away for any length of time is strange. The Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta, who journeyed 70,000 miles across much of the 14th-century Islamic world, wrote that “traveling gives you home in a thousand strange places, then leaves you a stranger in your own land.” I’d venture that all travelers, whether they have been away for years, months or only weeks, know something of this estrangement. What gap year student hasn’t returned from their rite-of-passage journey to find that the “gap” now lies between them and their former life? This peculiar dislocation — a kind of out-of-body experience — might wear off after several days, or it might last much longer.

Returning home after being away for any length of time is strange. The Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta, who journeyed 70,000 miles across much of the 14th-century Islamic world, wrote that “traveling gives you home in a thousand strange places, then leaves you a stranger in your own land.” I’d venture that all travelers, whether they have been away for years, months or only weeks, know something of this estrangement. What gap year student hasn’t returned from their rite-of-passage journey to find that the “gap” now lies between them and their former life? This peculiar dislocation — a kind of out-of-body experience — might wear off after several days, or it might last much longer. Determining whether someone has Alzheimer’s disease usually requires an extended diagnostic process. A doctor takes a patient’s medical history, discusses symptoms, administers verbal and visual cognitive tests. The patient may undergo a PET scan, an M.R.I. or a spinal tap — tests that detect the presence of two proteins in the brain, amyloid plaques and tau tangles, both associated with Alzheimer’s. All of that could change dramatically if new criteria proposed by an Alzheimer’s Association working group are widely adopted. Its final recommendations, expected later this year, will accelerate a shift that is already underway: from defining the disease by symptoms and behavior to defining it purely biologically — with biomarkers, substances in the body that indicate disease.

Determining whether someone has Alzheimer’s disease usually requires an extended diagnostic process. A doctor takes a patient’s medical history, discusses symptoms, administers verbal and visual cognitive tests. The patient may undergo a PET scan, an M.R.I. or a spinal tap — tests that detect the presence of two proteins in the brain, amyloid plaques and tau tangles, both associated with Alzheimer’s. All of that could change dramatically if new criteria proposed by an Alzheimer’s Association working group are widely adopted. Its final recommendations, expected later this year, will accelerate a shift that is already underway: from defining the disease by symptoms and behavior to defining it purely biologically — with biomarkers, substances in the body that indicate disease. While one segment of Silicon Valley lamented the perpetual absence of flying cars, another, it turns out, was quietly building them—or, at least, something flying-car adjacent. Just three months after the Founders Fund manifesto appeared, a Canadian inventor named Marcus Leng invited his neighbors and a couple of friends to his rural property, north of Lake Ontario. Leng was in his early fifties, with a bowl cut of coarse graying hair. He instructed his guests to park their (conventional) cars in a row and cower behind them. He strapped on a helmet and boarded a device that he’d built in his basement. It had a narrow single-seat chassis and two fixed wings, one in front and one in back, each with four small propellers. It was at once sleek and ungainly, as if a baby orca had been hitched to two snowplows. Observers described it, for lack of a better comparison, as looking like a U.F.O. Leng called it the BlackFly.

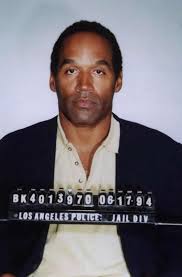

While one segment of Silicon Valley lamented the perpetual absence of flying cars, another, it turns out, was quietly building them—or, at least, something flying-car adjacent. Just three months after the Founders Fund manifesto appeared, a Canadian inventor named Marcus Leng invited his neighbors and a couple of friends to his rural property, north of Lake Ontario. Leng was in his early fifties, with a bowl cut of coarse graying hair. He instructed his guests to park their (conventional) cars in a row and cower behind them. He strapped on a helmet and boarded a device that he’d built in his basement. It had a narrow single-seat chassis and two fixed wings, one in front and one in back, each with four small propellers. It was at once sleek and ungainly, as if a baby orca had been hitched to two snowplows. Observers described it, for lack of a better comparison, as looking like a U.F.O. Leng called it the BlackFly. The two weeks spanning the O. J. Simpson verdict and Louis Farrakhan’s Million Man March on Washington were a good time for connoisseurs of racial paranoia. As blacks exulted at Simpson’s acquittal, horrified whites had a fleeting sense that this race thing was knottier than they’d ever supposed—that, when all the pieties were cleared away, blacks really were strangers in their midst. (The unspoken sentiment: And I thought I knew these people.) There was the faintest tincture of the Southern slaveowner’s disquiet in the aftermath of the bloody slave revolt led by Nat Turner—when the gentleman farmer was left to wonder which of his smiling, servile retainers would have slit his throat if the rebellion had spread as was intended, like fire on parched thatch. In the day or so following the verdict, young urban professionals took note of a slight froideur between themselves and their nannies and babysitters—the awkwardness of an unbroached subject. Rita Dove, who recently completed a term as the United States Poet Laureate, and who believes that Simpson was guilty, found it “appalling that white people were so outraged—more appalling than the decision as to whether he was guilty or not.” Of course, it’s possible to overstate the tensions. Marsalis invokes the example of team sports, saying, “You want your side to win, whatever the side is going to be. And the thing is, we’re still at a point in our national history where we look at each other as sides.”

The two weeks spanning the O. J. Simpson verdict and Louis Farrakhan’s Million Man March on Washington were a good time for connoisseurs of racial paranoia. As blacks exulted at Simpson’s acquittal, horrified whites had a fleeting sense that this race thing was knottier than they’d ever supposed—that, when all the pieties were cleared away, blacks really were strangers in their midst. (The unspoken sentiment: And I thought I knew these people.) There was the faintest tincture of the Southern slaveowner’s disquiet in the aftermath of the bloody slave revolt led by Nat Turner—when the gentleman farmer was left to wonder which of his smiling, servile retainers would have slit his throat if the rebellion had spread as was intended, like fire on parched thatch. In the day or so following the verdict, young urban professionals took note of a slight froideur between themselves and their nannies and babysitters—the awkwardness of an unbroached subject. Rita Dove, who recently completed a term as the United States Poet Laureate, and who believes that Simpson was guilty, found it “appalling that white people were so outraged—more appalling than the decision as to whether he was guilty or not.” Of course, it’s possible to overstate the tensions. Marsalis invokes the example of team sports, saying, “You want your side to win, whatever the side is going to be. And the thing is, we’re still at a point in our national history where we look at each other as sides.” Joseph H. Shieber, April 7, 2024 of Wallingford, PA. Beloved husband of Lesa Shieber; proud father of Samuel and Noa; loving son of Benjamin and Eileen Shieber; devoted brother of William (Rebecca) Shieber and Jonathan (Kathleen) Shieber.

Joseph H. Shieber, April 7, 2024 of Wallingford, PA. Beloved husband of Lesa Shieber; proud father of Samuel and Noa; loving son of Benjamin and Eileen Shieber; devoted brother of William (Rebecca) Shieber and Jonathan (Kathleen) Shieber. As the saying goes, if you believe only fascists guard borders, then you will ensure that only fascists will guard borders. The same principle applies to scientists working on nuclear weapons. If you believe that only Strangelovian warmongers work on nuclear weapons, you run the risk of ensuring that only such characters will do it.

As the saying goes, if you believe only fascists guard borders, then you will ensure that only fascists will guard borders. The same principle applies to scientists working on nuclear weapons. If you believe that only Strangelovian warmongers work on nuclear weapons, you run the risk of ensuring that only such characters will do it.

A new study has revealed a troubling development in the state of Maryland: while murder rates fluctuated between 2005 and 2017—first trending downward, then increasing for a few years—the homicides recorded during that period have grown steadily more violent the entire time.

A new study has revealed a troubling development in the state of Maryland: while murder rates fluctuated between 2005 and 2017—first trending downward, then increasing for a few years—the homicides recorded during that period have grown steadily more violent the entire time.

Consider again the wooden desk. It was once part of a tree, like the ones outside your window. It became a bit of furniture though a long process of growth, cutting, shaping buying and selling until it got to you. You sit before it as it has a use – a use value – but it was made, not to give you a platform for your coffee or laptop, but in order to make a profit: it has an exchange value, and so had a price. It is a commodity, the product of an entire economic system, capitalism, that got it to you. Someone laboured to make it and someone else, probably, profited by its sale. It has a history, a backstory.

Consider again the wooden desk. It was once part of a tree, like the ones outside your window. It became a bit of furniture though a long process of growth, cutting, shaping buying and selling until it got to you. You sit before it as it has a use – a use value – but it was made, not to give you a platform for your coffee or laptop, but in order to make a profit: it has an exchange value, and so had a price. It is a commodity, the product of an entire economic system, capitalism, that got it to you. Someone laboured to make it and someone else, probably, profited by its sale. It has a history, a backstory. All of this is the case, but none of it simply appears to the senses. Capitalism itself isn’t a thing, but that doesn’t make it less real. The idea that all that there really is amounts to things you can bump into or drop on your foot is the ‘common sense’ that operates as the ideology of everyday life: “this is your world and these are the facts”. But really, nothing is like that: there are no isolated facts, but rather a complex, twisted web of mediations: connections and negations that transform over time.

All of this is the case, but none of it simply appears to the senses. Capitalism itself isn’t a thing, but that doesn’t make it less real. The idea that all that there really is amounts to things you can bump into or drop on your foot is the ‘common sense’ that operates as the ideology of everyday life: “this is your world and these are the facts”. But really, nothing is like that: there are no isolated facts, but rather a complex, twisted web of mediations: connections and negations that transform over time.

The Chilean-American author

The Chilean-American author

Is there such a thing as tasting expertise that, if mastered, would help us enjoy a dish or a meal? It isn’t obvious such expertise has been identified.

Is there such a thing as tasting expertise that, if mastered, would help us enjoy a dish or a meal? It isn’t obvious such expertise has been identified. It’s a book about how our political system fell into this downward spiral—a doom loop of toxic politics. It’s a story that requires thinking big—about the nature of political conflict, about broad changes in American society over many decades, and, most of all, about the failures of our political institutions. (2)

It’s a book about how our political system fell into this downward spiral—a doom loop of toxic politics. It’s a story that requires thinking big—about the nature of political conflict, about broad changes in American society over many decades, and, most of all, about the failures of our political institutions. (2)