Click here to read this mailing online.

|

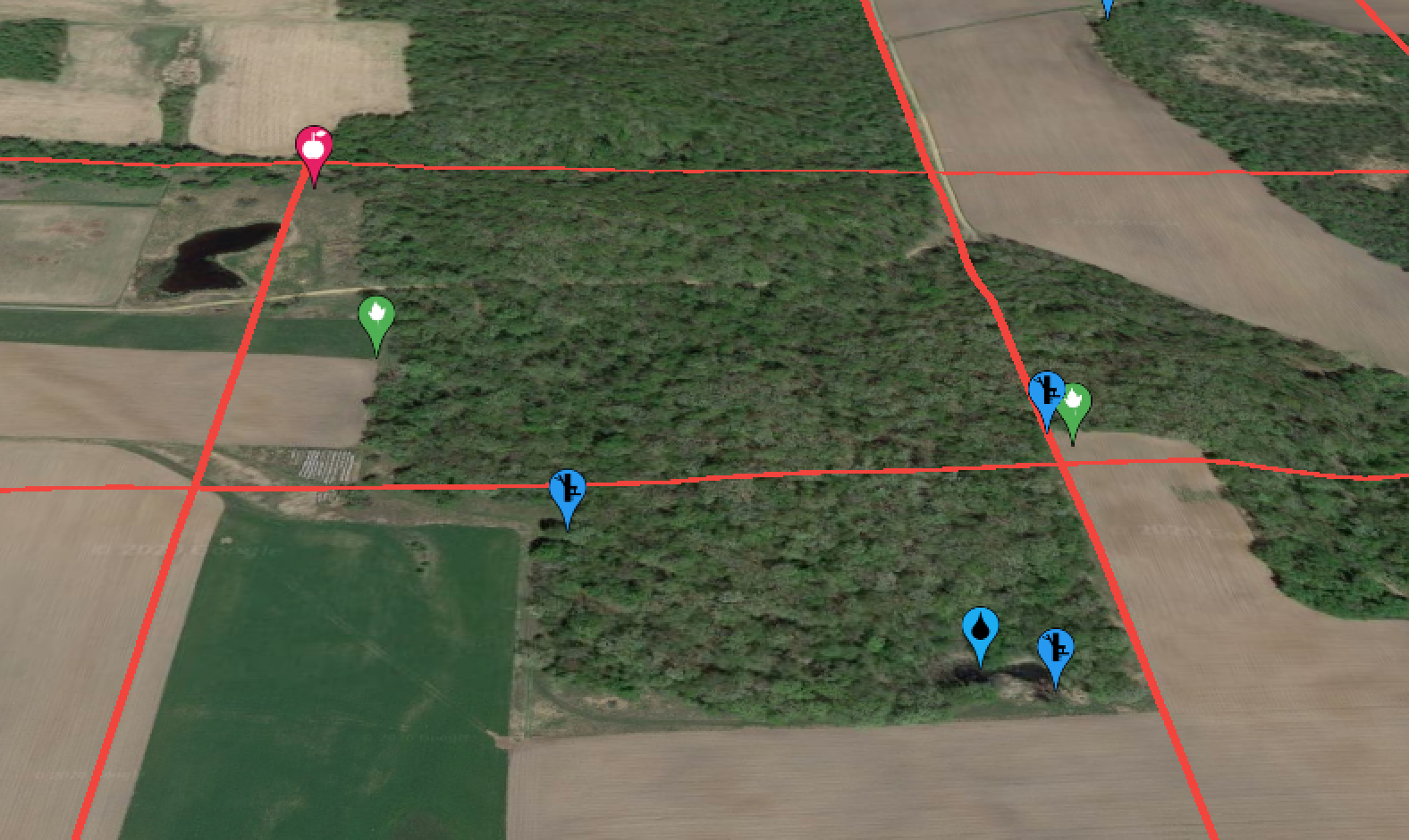

Tommy’s Boys: A Crew of New England Hunters Copes with Loss by Driving Deer Steve Powers (left) and Jeff Hamilton prepare to man their post for a deer drive. Rob Howard “C’mon, Beagle. Get your act together and come up with a damn game plan… Time’s a – wasting… Tommy would never have put up with this sitting-around-camp crap when there are deer out there to hunt.” George Wise’s good-natured cajoling instantly hits its mark, somewhere deep down in Marty Cormier’s gut. Although the scolding was lighthearted, the resulting angst is palpable. As he pores over topo maps and aerial photos, Marty, aka Beagle, calculates the next move. The job of Hunt Master is tough duty any day of deer season, but it’s Herculean when you’re tasked with casting 15 to 20 hunters across hundreds of acres of generally featureless public land. It’s all the more confounding when it’s mid-December, the deer have been pushed for weeks, your crew is toting muzzleloaders, and you’re trying to live up to the reputation of the Super Beagle.  The Loss of a LeaderIt was Wise who had dubbed Tommy Cormier, Marty’s younger brother, “Super Beagle” back in 2002 for his uncanny knack of getting deer up on their feet and headed in the direction of one of his buddies waiting in the woods for driven deer to sluice past him. It was the same year that Tommy shot a giant buck on a hill called Round Top not far out of town. “Just think about beagles for a second,” Wise explains. “What do they do? They zigzag through the thickest damn cover in the woods and get stuff up and moving–and then they chase like hell. Well, that was Tommy. What else happens? People follow beagles through the woods. I bet that half the kids in town learned how to hunt because they followed Tommy through the woods. He just wanted to teach them how to hunt. Hunting wasn’t what he did–it’s who he was.” “There was no keeping him out of the woods,” says Tommy’s father, Ray. “If deer or turkey season was open, you wouldn’t see him–he was gone. And whether it was Josh and Steven [Tommy’s sons], or his nephews and nieces, he’d take some kid fishing or wake them up in the dark, get them dressed in warm clothes, and take them out in the woods to scout for deer and turkeys. He got them involved almost as soon as they could walk.” But then, it all went to hell. Tommy Cormier, just 36 years old, was gone. The father of two young boys died tragically in an ATV wreck that forever changed the lives of the survivors.  When they laid Tommy to rest, cars lined both sides of Route 57 for half a mile. Mourners young and old walked arm in arm up the long hill to the family plot. You couldn’t miss it–it’s next to the giant oak tree, the one that consistently drops acorns and draws in turkeys and deer. And you couldn’t mistake Tommy’s Boys. They were the ones dressed in camo. The late Hank Zelek’s old Quonset hut provides a fitting backdrop for Tommy’s Boys in a group shot taken between drives. They might not have known it then, but this handful of men was being transformed from a simple ragtag group of buddies who occasionally hunted together into a tightly bonded crew of hunters. Their collective mission is to one day shoot a buck “as big as Tommy’s” in country that has historically had few big deer, keeping the Super Beagle’s spirit alive in the process. That spirit is what drives them today, what makes them work long hours in the blue-collar world of construction, plumbing, concrete fabrication, and engine repair during spring and summer so that they can take time off each fall to hunt. It’s why, even though few of Tommy’s Boys live more than 10 miles away, they–as Tommy always had–headquarter their seasonal deer camp in Hank Zelek’s old Quonset hut, which has no running water and only a woodstove for heat. And it’s also why kids in oversize blaze-orange hats and vests are always a part of camp. Tommy wouldn’t have had it any other way. It’s his memory that provides them all with the motivation to walk the woods right up until the season’s bitter end on New Year’s Eve, continually trying to outsmart whitetails like Tommy tried to teach them. “He was just special,” says Marty. “As a person, everyone just instantly took a shine to him. As a hunter, well, Tommy could pattern deer like nobody’s business. He saw stuff that we didn’t. With that big buck he killed, he somehow knew exactly where the deer would be on opening morning. So that’s where we went and that’s where he was.”  Bucks Like You Read AboutBy Boone and Crockett standards, no one will ever confuse the deer of southern New England with those of Wisconsin or Kansas. Historically, if hunters in the Northeast wanted to shoot a top-end buck, they’d load up the truck and head for Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom or Maine–snow-tracking country. Occasionally, someone would come home with a buck to boast about, but they’d most likely be bragging on body size rather than antler mass. But lately, southern New England has come roaring through on trophy-buck bragging boards. It may well have started the year of Tommy’s buck–a 10-point, 200-pounder that he often described as “a deer like you’d read about”–and the trend has continued. In the fall of 2011, for example, a 226 7/8 non-typical set a new Connecticut bow standard, followed last fall by a 198-inch non-typical bow kill and a 210-inch non-typical muzzleloader kill in Massachusetts. The relatively new phenomenon of big southern New England deer is most likely due to a number of factors, including relatively easy recent winters, a lack of hunting pressure, and a couple of record–setting mast crops. “Deer Week,” as many continue to refer to deer season, used to last just five days and consisted mostly of a scattering of distant shots and an occasional glimpse of a white tail. The fortunate few who scored hung their spikes, forkhorns, and does in front of their camp with chest-jutting pride.  “If you saw one deer all week, you were lucky,” explains Charlie Pease, who has spent 40 years hunting these same woods. “I wouldn’t say that the deer hunting is great now, but at least you’ve got a chance at seeing a really good buck.” Which is why Marty studies his topos harder than he ever did his schoolbooks. “What would Tommy do?” he says under his breath. “That little s*$@ always knew where to go and how to drive it. If he got a deer up and running, he’d stay on it and eventually get it out in front of someone–unless he shot it himself. Someone would get a shot, though.” At least a dozen men identify themselves as Tommy’s Boys, but the core of the group are his brother Marty; the veteran Pease and his son, Chuck; Tommy’s closest friend, Rich Hamilton; Brian McCuin; Maine regulars Wise and Steve Powers; and relative newcomer Billy White. “We’re doing Round Top,” Marty finally announces. “We pushed deer out of there yesterday, but that doesn’t mean anything. They probably just circled around us and went right back into the thick stuff. Hell, we’d do it with Tommy every day of deer season sometimes. I’ll drive it with Billy, Rich, and Brian. Charlie can place the standers. Let’s go.”  Moving Past a TragedyThe “yesterday” of Marty’s charge was a day no one in the group, or the country, will ever forget–the day of the senseless massacre of teachers and schoolchildren in Newtown, Connecticut. While the group of muzzleloader-toting hunting buddies, some of whom had let their young kids skip school for the day, had been pushing a patch of timber, an unimaginable horror was taking place just 50 or so miles away. Word broke when someone checked his cell phone as hunters gathered around the deer-less bed of Tommy’s old Dodge Ram pickup. “Do you think we should go down there to help? I mean, what the hell is going on? It’s got to be terrorists,” someone muttered, grappling to make sense of the incomprehensible. Everyone searched for answers, with Tommy’s hunting truck a fitting centerpiece to mourn those taken so young. “What now? What should we do?” “I think we need to do another drive,” Marty responded. “Grab the kids and let’s hunt.” It was all anyone knew to do. By the time the hunters return to Round Top the next day, the full horror is known. Marty, in Tommy’s hunting truck, leads the way down the old two-track through the woods onto state land. “Let’s go, boys, we’re here,” he says. “And please, will you guys shoot something like you read about this time?” The sight of the blaze-orange troop piling out of the other vehicles would have brought a familiar broad grin to Tommy’s face. There seem to be more kids than there are adults–few old enough to carry their own muzzleloader. Along for the hunt are Tommy’s teenage sons, Josh and Steven.  With Marty in the lead, Tommy’s Boys tackle Round Top. Drivers are to push the cover uphill while Charlie Pease places standers along the crest of the quarter-mile-long ridgetop, telling each precisely where to stand, which way to face, and how long the drive would take. Two hours later, the Round Top drive is done—no shots fired, no deer seen, no surprise there. Tommy’s Boys once again gather around the bed of the empty pickup truck, as they had the day before. “Yeah, it never really works out the way you want it to,” Pease says. “But what the heck, you never know.” “So what now,” someone asks. “What do we do now, Mart?” “Well, jeez, guys,” the Beagle says. “Grab the kids and let’s go do another one. It’s what we do.” It’s what Tommy would have done. And it was all anyone knew to do. This story originally ran under the title “Tommy’s Boys” in the December/January 2014 issue of Outdoor Life. The post Tommy’s Boys: A Crew of New England Hunters Copes with Loss by Driving Deer appeared first on Outdoor Life. Map These 5 Food Sources to Find Deer All Season Long Inventory the available food sources on your property with a mapping app like HuntStand. HuntStand Right now, the land where you deer hunt should be covered with groceries. Deer groceries, that is. Late summer and early fall is the time of plenty in the deer woods, and the deer are busy packing on the pounds. But not with just any old food—deer can be picky eaters. They like certain browse better than others at certain times of the year (biologists refer to them as “concentrate selectors”). So if you want to hunt smart this year, inventory the available food sources on your property, and hunt those spots when deer are craving those foods most. 1. Acorns Draw a CrowdAcorns are high on the list for deer—especially white oak acorns compared to red oak acorns. The acorns have been “on” the last few years on my deer hunting property, and their abundance in my area had the deer dispersed over many square miles. What’s more, this dispersal lasted throughout the entire hunting season. Nothing we planted, nor any other wild food source, seemed to matter. It was acorns or nothing, and it was almost impossible to predict where the deer would be feeding next. The abundance of food was good news for the herd, but infuriating for us hunters. This year, however, our acorn production is slim and spotty. Only a few trees are producing, which takes the guesswork out of figuring where deer will be when the acorns start to drop (which is right about now). I know where I’ll be hanging out when bow season opens in two weeks. 2. Fruits Are a FavoriteIt’s no secret that deer love apples and other fruits, but they won’t start hitting the apples until acorns are hard to come by and apples start becoming available. Some trees lighten their load midway through the summer growing season, but most wait until they become fully ripe before dropping, which can happen in late fall. I know where our “late droppers” are located, and often find late-season deer under their limbs, pawing through the snow looking for a winter treat. Most fruits are high in sugar content and deer—just like people—seem to crave sugar. Ripe berries also seem to have the same attraction. The trick is to know where the fruits grow and when the deer will be on them. 3. Is Corn Really King?Each year we plant a few acres of corn for the deer. Our deer don’t begin working our corn until late fall, when most of the sweet, soft mast in the timber has been cleaned up and the green plots have been hit hard. We hunt the corn late in the season when deer shift from those remaining sources of high-carb “hot” foods, which help them pack on the pounds for the long winter ahead. Their preference for corn in your neck of the woods will depend on weather and what other foods they have to choose from. 4. Green Plots Are GreatOur food plots offer tons of browse from spring through fall each year. But the deer are still selective about which plots or cultivars they’re snacking on at any given time. It’s not uncommon for plots with multiple plant varieties to have only one plant being eaten (for, say, two weeks) before the deer switch to another. Our clover plots receive high traffic in the early spring and late fall when conditions are cool and wet, while our chicories get hit heavily in summer. When we first started planting brassicas (decades ago), our deer waited for a freeze before flocking to the plots where we planted rape, turnips, and the like. But over the years, they seemed to become keener on early season plantings. Green plot grain plantings always seem to be our plots of last resort, and are used later in the year when the deer are beginning to browse heavily. It pays to know what’s in your green plots and when your deer key in on what. 5. And Then There’s BrowseDon’t underestimate browse when it comes to feeding deer. A woodlot can produce a thousand pounds of deer food per acre if it has been thinned to the point where the sun hits the grounds and natural vegetation starts popping up. On the other hand, over storied woodlots with no sun on the ground produce next to nothing. Field edges produce tons of food in the form of natural vegetation shrubs, forbs, and low-growing plants. Research has shown that native vegetation comprises an important part of a deer’s diet, even in areas with plenty of agricultural crops available. They don’t seem to key in on browse until the most preferred foods have been eaten up, but they definitely do use browse a good deal as they move to and from concentrations of preferred foods and natural vegetation is what gets most deer through winter Our deer go for fruit trees first, and then move on to any berry bushes they can find. They love maple leaves, and the first inch or two of new growth. They always prefer the first inch of new growth to lignin-laden old growth (can be as big around as your pinky finger). Our deer won’t touch beech or hemlock but that can vary with the property. Dr. Grant Woods is fond of saying, “Deer are slaves to their stomachs.” Truer words were never spoken. Savvy hunters know that the food on their hunting varies each year, and they also know which foods will be available when. And eventually they’ll learn the preferences of their local deer. Of course, all this varies depending upon when things are planted and the mercy of Mother Nature. Super savvy hunters will map their food sources and refer to it often when planning their hunting strategies. A little boot leather (and some time with an aerial photo) will get you to the skinning shed faster than you can look up “concentrate selectors.” The post Map These 5 Food Sources to Find Deer All Season Long appeared first on Outdoor Life. How to Mess Up 4 Dynamite Early-Season Stand Sites A well-hidden bow setup on the edge of a small food plot. Mark Kenyon When conditions are right, hunting pressure is low, and you correctly hunt the perfect location–early-season whitetail hunting can be a slam-dunk. But getting all of those variables in your favor is much easier said than done. While much of the emphasis on early-season success is placed on being in the right spot, if you don’t get the rest of the puzzle in place you’re in for some frustrating hunts. Here are four of those dynamite early season stand sites, and how you could mess it all up if you don’t look at the whole picture. 1. Observation StandsThe most likely way to screw up an observation stand is by simply not using one. If you don’t already have a killer early-season stand location picked out, rather than diving into a random area, you might be better served by sitting in an observation stand to kick off the season. Set up in an area that’s far enough away from your expected deer hotspots, so as to avoid putting undue pressure on the herd, but also placed somewhere you can observe likely deer movement. After a few sits, you’ll hopefully be able to identify exactly where you need to be to intercept the deer you’re after, and at that point, you can move in for the kill. 2. Water HoleIf you’re dealing with an early-season heat-wave, few stand sites are better than an isolated water source close to bedding cover. But make sure you’re saving these hunts for the most likely days of daylight use. While a water source can be visited anytime, it will be those hot early-season days that you’ll have the best chance. Wait for those heat-wave conditions and then set-up within shooting range of a small pond, water tank or man-made waterhole. 3. Small Food PlotA small food plot located tight to good bedding cover can be a high-odds, early-season stand site. But it’s also an incredibly easy spot to screw up. If you’re hunting right on a food plot, your greatest challenge will be getting in or out of that stand without spooking deer off the plot. Make sure to have a stealth approach into your stand if your hunts coincide with a time of use for local deer. And if you can’t get in without spooking feeding whitetails, consider a new location or setting up farther off the food source. 4. Mast TreesFind a couple loaded apple trees or an oak flat showering acorns in the early season and you’re undoubtedly going to see deer activity. But be warned that these mast-producing trees won’t always produce good hunting opportunities. The risk here is assuming that an apple, oak, persimmon or other mast producer will always produce – because that’s not the case. Make sure you do some type of speed-scouting in late summer to check if your early-season food source is actually holding acorns, apples or whatever the mast might be. If they’re not producing that year, you’d be better served to try a different area. The post How to Mess Up 4 Dynamite Early-Season Stand Sites appeared first on Outdoor Life. 7 Steps for Taking Better Summer Trail Camera Photos A summer buck in velvet, captured with a perfectly positioned trail camera. Mark Kenyon As whitetail bucks across the country start packing on antler inches, millions of whitetail addicts will be sneaking into the woods with trail cameras in tow, hoping to catch a photo or two of the local giant. And if you make sure to follow these seven steps, you can be the guy or gal that actually gets those photos—and maybe an opportunity to tag a great buck when the season opens. 1. LocationThe first step to trail camera success in the summer is setting your trail cam in the right location. At this time of year, food is the top priority for deer, so place your cameras close to prime summer food sources like soybean, alfalfa, clover, and other green fields. 2. AccessWhen considering the location for your cameras, also keep in mind how you can access them in the future. Place your cameras in easy-to-access locations, where you can walk in along a field edge or drive directly to the camera, as this will limit the pressure you put on the deer. A common mistake is to set summer cameras too deep into the timber or too close to bedding areas, which ultimately educates deer and pushes them away from your cameras. 3. PositioningOnce a location is set, you have to properly position the camera. Ideally you’ll want your camera facing north or south to avoid capturing washed out photos during sunrise or set. You’ll also want to consider the height at which you set the camera. On properties where you’re dealing with other hunters, you might want to place your camera high in a tree and angled down, to avoid being seen by any passersby. This is also a good idea in areas of high hunting pressure, where mature bucks are more easily spooked by obviously placed cameras. On the other hand, if you’re not worried about theft or spooking deer, place your camera as level as possible and at about deer-eye level. 4. Digital Set UpThere’s nothing worse than arriving to check a camera weeks after setting it up and finding that it took no photos. So take time to understand how to properly adjust the settings on your camera, then use fresh batteries and format your SD card in the camera before leaving. And if you plan on leaving your camera for an extended period of time, be sure to set your capture and interval modes with that plan in mind. These settings determine how many photos at a time your camera will take and how long an interval there will be between photo sequences. I like to set my camera to take two photos per trigger and then wait one minute before triggering again. This keeps me from filling up an entire card because a doe and her fawn are sitting in front of my camera for 10 minutes. 5. AttractantTo ensure maximum trail cam photos, I recommend a two-punch approach to attracting deer in front of your camera. Where legal, use some kind of attractant with a strong odor, which will draw deer to the camera site quickly. This might be something like corn, apples, or a manufactured attractant like Big & J’s BB2. I then like to place a longer-lasting mineral alongside that attractant, which is what will keep deer returning to the camera site well after that corn or other material is gone. Mineral products like Trophy Rocks, Whitetail Institute’s 30-06, and many others will fit the bill. 6. Return TripsA properly located and set-up camera can get you on the right track for quality trail camera pictures, but if you check your camera too often, it’s all for naught. This is probably the biggest mistake hunters make when it comes to trail cams: We often give in to the temptation to check our cameras too frequently, and end up educating deer to our presence. Practice self-restraint and give your cameras about two weeks between return trips—and even longer if you can handle it. 7. Scent ControlAnd when you do check those cameras, practice all the same scent control that you do during hunting season. Spooked deer during the summer, especially mature bucks, will avoid the area and your cameras. So wear scent-free clothes and boots, and spray down with a scent eliminator before entering the field. I also wear gloves when handling my trail camera and spray that down after I finish swapping out SD cards. The post 7 Steps for Taking Better Summer Trail Camera Photos appeared first on Outdoor Life. 3 Steps for Tagging a Monster Early-Season Buck A big early-season buck checks his back trail. John Hafner Every September, in every corner of whitetail country, it happens: While the majority of us are poring over the November calendar trying to figure out which days of the rut to hunt, word leaks out about someone who’s already put a monster buck in the books. If you think that it is all just anecdotal hearsay, consider this: From 2003 to 2013, 19 percent of all whitetail bucks entered into the Pope and Young Club record book were taken on or before October 15. In Outdoor Life’s own Deer of the Year program, nearly a quarter of all whitetails entered were shot before October 15. Why the early-season success? The answer involves a bit of whitetail biology, combined with equal parts hardcore scouting and tactical savvy. Here’s how to do it yourself this season. Step 1: Find Where He Eats The beginning of hunting season has whitetails in the feeding mode of their feed-breed-feed life cycle. Here’s how it works: In late summer, whitetails chow down on the most nutritious foods they can find. According to Kip Adams, wildlife biologist and QDMA’s director of conservation, deer are genetically programmed to set up defined home ranges near highly nutritious food sources and heavy bedding cover. They move as little as possible in order to pile on the poundage in preparation for the rut—and winter—that follows. “Whitetails are all about putting on weight in the early season,” says renowned whitetail authority Charles Alsheimer. “In fact, they’ll gain a full 20 percent of their weight from August 15 to October 15. The early-season hunt, therefore, should be all about hunting food sources. The deer feed and bed, then bed and feed until the rut ramps up and the need to breed dominates their lives. But early on, they are eminently patternable.” At some point in late summer (usually September), soft and hard mast becomes available, resulting in a shift in feeding patterns. First are soft-mast crops like apples, pears, persimmons, and a host of sugar-rich berries. Hard-mast crops like acorns and beechnuts, which are rich in carbohydrates and fats, are next, providing the stuff that builds reserves for the rut and winter ahead. But killing a good whitetail buck in this pre-rut period involves more than understanding simple biology. It’s also about finding a place that is likely to hide a mature animal.  Step 2: Learn What He DoesEarly-season devotees know which preferred foods are available and when deer seek them out. They also know precisely how to scout food sources to locate the buck they want. However, not all of them go about their business the same way. Kansas outfitter Larry Konrade is one of the most successful whitetail outfitters in the country. Konrade, a big-buck specialist, says his favorite season to target trophy whitetails is during his state’s September and early-October bow and muzzleloader season. Konrade’s singular focus is getting his hunters in front of trophy bucks, and he delivers the goods year after year. Most of his hunters have opportunities at 170-inch bucks inside of 100 yards. One of the biggest they’ve killed grossed 190 2/8. “Our deer go from bedding areas to feeding locations and back again,” says Konrade. “They are very patternable. All you need to do is watch them, figure them out—and get on them.” Private-land hunters, like Konrade, are often able to identify specific bucks to hunt by staking out planted-food sources. “I can pretty much say that every deer we hunt has been patterned,” explains Konrade. “We use a lot of cameras and spend a lot of time in the field to find out what the big bucks are feeding on and how to hunt them. But more often than not, we’ll be watching a deer through a spotting scope from a distance of almost a mile or more. We have a lot of open country here in the Midwest, so we do a lot of spotting scope work.” For public-land hunters, the chore is considerably more difficult. Not only is it a lot tougher to locate a specific buck to hunt on public land, but it’s also tougher to pattern him.  Michigan’s Chris Eberhart has formulated his own plan. Eberhart, who has lost count of the number of mature bucks he has killed on public land, prefers not to identify a specific buck to hunt. It can be done, but he sees it as a low-percentage game. Instead, he scrutinizes topo maps and aerial photos in search of remote pockets of habitat on public land where he knows big bucks will be—places where other hunters are unlikely to tread. If he finds a food source nearby, he knows that his chance at an early-season buck will come. Acorn-dropping white oaks, abandoned apple orchards, or even a single producing apple tree amid thick cover are his favorite stand locations. “I really like areas that are isolated by water or swamps,” Eberhart says. “Deep gulches and super-steep slopes are also good places to hunt mature bucks. I mark areas like this the season before or in early spring. “Scouting too close to the season is a great way to ruin the hunting,” he adds. “For public-land bucks, the need to feed is secondary to the imperative to stay alive. I scout the year or at least six months before I plan on hunting an area. All the mature bucks will be nocturnal in one to two days if they feel pressure. The way you pattern big bucks is to find an area where no one goes, and that’s where they will be. The sign will be there from the year before.”  Although he owns some land in New York State, bowhunter Jason Ashe also targets food sources on nearby public-hunting areas early in the season. “I look for early-season food on public land just like I do on private property,” says Ashe. “The only difference is, I didn’t plant it. The state forests I hunt have been logged over the years, and these areas are covered with the berry bushes and young growth that deer love. I’ve found old farm sites with honeysuckle vines and all kinds of grown-up stuff that deer love to feed on. There are always some old apple trees around somewhere—you just have to put in the time scouting. These places are right there on the map. “Another thing to keep in mind is that public-land deer definitely use private croplands. A deer will travel a mile or more to get to a field of beans or a patch of alfalfa. They may feed all night out in the open, but by daybreak they will be well back in the woods, where no one can reach them. Most guys hunt too close to the road. That’s why I study aerial photos to find human travel routes, then map them. This tells me where I don’t want to be. I like to set up on natural terrain funnels and crossings, and catch deer when they are coming back to their bedding sites.” Step 3: Know When to Take HimWhen the green flag comes down on opening day, there are two schools of thought on big bucks: Hunt them easy or hunt them tight and hard. The choice typically depends on the “where” of your specific hunting equation. Savvy private-land hunters are all about keeping their targeted bucks calm and relaxed. They do not intrude, but rather nibble away at the edges of a buck’s territory in hopes of catching him with his guard down. They make their move when the time is right but avoid unnecessary pressure at all costs. “During the early season, big bucks are still using open fields and can be easy to pattern, but that doesn’t mean they are easy to hunt,” says Bass Pro Shops’ Jerry Martin, who is a big fan of the pre-rut. “You can hunt a mature buck from the same stand for maybe one or two days, but then he’ll be onto you. You can’t be traipsing all over the woods and expect to kill him. I’m real careful to play the wind right and keep noise to a minimum–it’s critically important. Anything new or strange will alert a big buck in a hurry. Clinks and clanks are a dead giveaway. A buck that has been around for a while knows all about strange noises and smells. He may start the season relaxed, but it doesn’t take much to put him on alert.” “We are super cautious to not pressure them,” says Konrade. “A big old buck won’t put up with it for long. We set and check cameras only when the deer are bedded.”  On my 500-acre property in Upstate New York, my son Neil (pictured above) and I also go to great lengths to avoid polluting the woods with human scent. We try to provide the deer with all the comforts of home—and surprising them in their bedrooms is not one of them. Our neighbors hunt hard and lay down plenty of tracks and scent cones that alert the nearby deer to their presence, and we try to use that to our advantage. We give the deer plenty of room and try to provide them with sanctuary areas where they can bed and feed without harassment. They pile into our safe haven as the surrounding pressure builds. We may move in on them during the rut, but we try to avoid too much pressure during the early season. Many public-land hunters, like Jason Ashe, prefer to hit them with everything they’ve got. “I hunt deep and I hunt tight,” says Ashe. “I can’t and don’t worry about pressuring them by hunting bedding areas—they are already buggered up. I try to catch them heading back to their bedding areas or leaving just before dark. You have to get way in early and stay late.” Read Next: How Much More Antler Will Your Target Buck Grow Before Opening Day? Chris Eberhart hunts aggressively as well. He wants to be set up long before shooting light and will stay as late as legal light allows to arrow a late mover. “You have to find these areas, set up on them, and put in your time if you want to kill a mature deer on public land,” says Eberhart. “I hunt a cattail swamp on opening day. Bucks love the place. I carry in my waders and make my way onto a small, dry spot a couple of hours before daylight. It’s a great -early-morning spot to catch a buck heading back to safety in the gray light of dawn. “I also keep a book full of remote places like this to set up in. They all have one thing in common–and that is no hunting pressure. Big bucks know these places and are using them well before the season opens. I move right in on them, give ’em my best shot, and head out to another setup.” Whether you are on private or public land, the early season is all about how you hunt deer that are concentrating on food sources. Food can lead you to the biggest buck of your life—if you do it right. The post 3 Steps for Tagging a Monster Early-Season Buck appeared first on Outdoor Life. More Recent Articles |